Fiction:

"C-Town"

Articles on Cornell:

What I Miss About Cornell (The Cornell Daily Sun 9/28/06)

The Risley Sanction (The Cornell Daily Sun 2/5/03)

Ahead at the Finnish (Cornell Alumni News 1-2/94)

Franchot Tone and the Golden Age of Cornell Theater (Unpublished 1990)

“This Is Charles Collingwood” (The Cornell Alumni News 5/1990)

More April '69 Blues (The Cornell Daily Sun, 1989)

Talking the April '69 Blues (The Cornell Daily Sun 7/04/89)

Ruminations of an Ex-Space Cowboy (The Cornell Daily Sun 1/30/87)

On Closer Examination (Cornell Alumni News 9/80)

The Good Times (Cornell Alumni News 9/76)

Stopping Out (Cornell Alumni News 6/74)

Apathy (continued) (The Cornell Daily Sun 29/12/1973)

Where Is the Cornell Heart? (Cornell Alumni News 5/73)

Tacka-Tacka-Zonk! (The Cornell Daily Sun, 1972)

A.D. White Library

1920s Cornell post card

Class of 1972 Cornell desk book

Risley Hall overlooking Cascadilla Gorge

Green Dragon cafe

Collegetown wall, 2002

Great Hall, Risley

College of Architecture wall, 2002

Sunrise, Cornell plantations, Hanging Out class of 2009

Hanging Out class photo, 2011

JJ Manford '06

Gordon and JJ 2022

Dorrit's visit, 2003

Charles Collingwood '39 with Jackie Kennedy

Franchot Tone Cornell '27 with Bette Davis

Welcome!

If you are a Cornellian, you will doubtless recall the Cornelliana section of the Andrew Dickson White Reading Room of Uris Library, the section devoted to works about our alma mater. Well, here, in the 14 odd essays, squibs dating back to 1970, plus “C Town Blues,” the novel about “my” Cornell I serialized in “The Cornell Daily Sun” between 2004 and 2006 after I returned to The Hill to be artist in residence, is my Cornelliana room, so to speak. Or should I say ours: I would like to think that Cornellians from every modern era from the 1920s forward will find something of interest amongst the diverse offerings here, which in addition to my fictional and non-fictional depictions of the various eras of Cornell history which I lived through and/or witnessed, also include several of my own historical forays into the Cornell of the 1920s and 1930s, when the likes of future Hollywood great Franchot Tone and famed CBS broadcaster Charles Collingwood skipped across the Arts Quad, for my first journalistic home, the late great Cornell Alumni News.

All told there are over 60,000 words archived here, all about Cornell. “Raise the chorus, speed it onward, Hail all Hail Cornell...”

Ah yes, Cornell. For me all roads lead to Cornell, my alma mater, my Golgotha, and the site of my resurrection; the site of my first great romance and most painful heartbreak; the place where I first learned my craft and practiced it; my north star, or at least the longest-lived one in my firmament.

Do I sound like I am getting carried away? Well, as anyone who went to Cornell, or has visited its otherworldly campus far above Cayuga’s waters knows, to paraphrase the university’s stirring aforementioned anthem, which I recall being forced to sing at the first home football game at grand old Schoelkopf Stadium, the sweeping, gorge-bisected Cornell campus in upstate New York is that kind of place.

I had two Cornell careers, so to speak, which together extended slightly over two decades, or roughly half of my adult life, one much happier than the other. The first less happy, if not unfruitful one, my undergraduate career—if can be called that—began in 1968 when I matriculated in Cornell’s College of Art, Architecture and Planning and extended through my belated--and somewhat miraculous--graduation from the College of Arts and Sciences, to which I had transferred after a Kafkaesque term in the Division of Unclassified Students, Cornell’s version of Middle Earth, in 1973.

I call it miraculous because that rocky period saw me in nearly continuous trouble with the powers that be, namely the college’s all mighty Committee on Academic Records, which suspended me for a year after I achieved--if that is the word—an historic 0.0 cumulative average which briefly made me a culture hero in Collegetown, where I had been living in a tenement-like building on College Avenue with several other fallen Cornell men, and ordered me to leave Ithaca and get a job in the Real World if I hoped to have any chance of returning.

And so I did, in September, 1970. Whereupon my idiosyncratic academic ways, which entailed focusing on the courses I liked and letting the rest fall by the wayside along with my tendency to write eccentric, dadaistic papers, promptly got me into trouble with the dread Committee again, resulting in a Final Warning and another Warning, over the next few years, thus continuing the great tradition set by Kurt Vonnegut ’46 and other future Cornell scribes who spent a sizable fraction of their undergraduate years at the unbending Ivy on one sort of probation or another.

Put another way, Cornell University was not the right college for me. The fact that I had skipped a grade in high school and was only 17 when I matriculated—and an extremely immature 17—did not help matters. Nor did the fact that something called The Sixties was still going on, as well as the Vietnam War, and that Big Red was in the midst of the most turbulent period of its hundred year history, exemplified by the celebrated/infamous occupation of Willard Straight Hall, the student union, on Parents’ Weekend, by the enraged members of the Afro-American Society, who were later supplied arms by their righteous friends in the Students for a Democratic Society, of which I was a fringe member, an event which happened to take place in April of 1969, while I was treading water as an Unclassified student.

Which was not particularly helpful. Mind you, my Cornell undergraduate years weren’t a total wash out. Belatedly catching the writing bug, I did lay the groundwork there for my overlapping careers as journalist and contemporary historian, hanging out in Ithaca, which is a very good place to hang out, for two additional years, through the fall of 1975, interrupted by my first sojourn in Europe and beginnings as a foreign correspondent. I also wrote for the college’s wonderful, gloriously independent alumni magazine, the Cornell Alumni News, and its outstanding, Time Magazine trained editor, John Marcham ’50, shooting off passionately felt essays about The New Vocationalism and rapidly morphing student zeitgeist and all that, along with occasional forays into Cornell’s colorful history, including my favorite decade, the 1920s. And one memorable expose of CU’s dysfunctional-cum-non-existent advising system on which I took retroactive, journalistic revenge on my corporate-minded alma mater for allowing me and thousands of others over the years to fall from sight and sink beneath the academic waves as I did several years before, a publishing event that shook the powers that be, Committee(s) on Academic Records included: my first experience of the power of the press. (Alas such a feature would no longer be possible in the News’s toothless university-owned descendant.)

So, it seems, I wound up getting something out of my first, undergraduate/post-graduate Cornell life, after all.

Nevertheless when I finally departed The Hill for good—or so I thought—in 1975, seven long years after my wide-eyed arrival, and moved back to New York City, it was none too soon. Over the next two decades, I did take the five hour long bus from the Port Authority Bus Terminal back to upstate Ithaca now and then, after I had established myself as a freelance education writer writing for The New York Times and the like, including two memorable, short sojourns at Cornell’s quixotic Risley Residential College for the Creative and Performing Arts, including one, in 1989, when I worked on my first book, about local hero and one of my first bona fide heroes, Rod Serling, the creator of The Twilight Zone. (www.gordonsander.com/serling)

That gave me a chance to repair to my favorite undergraduate writing spot, the historic, gilt-framed portrait-lined Andrew Dickson White reading room of Uris Library overlooking Libe Slope—and the scene of my one great undergraduate literary triumph, winning first prize and $200--the equivalent of $1350 in 2023 terms--in the biannual book collection contest with my painstakingly curated collection of books from and about the 1920s and amusingly annotated accompanying bibliography, “A Personal Bibliography of The Jazz Age.”

Oh how I remember running back to the Collegetown apartment I shared with my then love, Christine A. Ryan ’74, check in hand, to celebrate that apotheosis. That was my Eighty Yard Run, the title of the famed Irwin Shaw story about a college football hero who keeps reliving his greatest moment, an impossible 80 yard touchdown run--also the inspiration for a 1950s tv play starring my all-time favorite actor, Paul Newman--as his sweetheart breathlessly watched on from the stands.

That was fun. Nevertheless my bittersweet memories of that earlier first Cornell life, including my traumatic break up with aforementioned Christine Ryan, my first great love, still festered, as did those of my late mother, who still remembered my traumatic suspension. “Cornell,” she would say for many years after whenever I happened to mention it. “I don’t want to hear that word!”

I certainly didn’t anticipate that I would actually return to Cornell and Ithaca—which I always loved—to live for an extended period of time.

But that exactly is what happened in September 2002, after I returned to Risley as artist in residence at the Castle, as Risley’s ancient crenelated home is known, and set up shop and home in the capacious ground floor suite. And proceeded to have the time of my life, simultaneously working on my second book, The Frank Family That Survived—the book which had emanated from the BBC Radio 4 series I had written and narrated in London the year before (see www.gordonsander.com/the-frank-family-that-survived)—while acting as in-house rabbi/godfather for my appreciative new flock of 190 odd student neighbors and surrogate children.

Best job I ever had. Writing and editing a newspaper for the college, “Panopticon,” hosting Twilight Zone marathons in the Central Living Room, “teaching” an all-night course-cum-walking tour of Ithaca-cum-poetry reading at dawn, you name it, I did it during my initial tenure as artist-in-residence. Did a pretty fair job of it too, witness the fact that the Risleyites changed the college constitution so that I could run in the election for an unprecedented second year for the competitive position, which comes with free room and board and run of the campus. Which I won by a sizable margin. That was a gratifying moment.

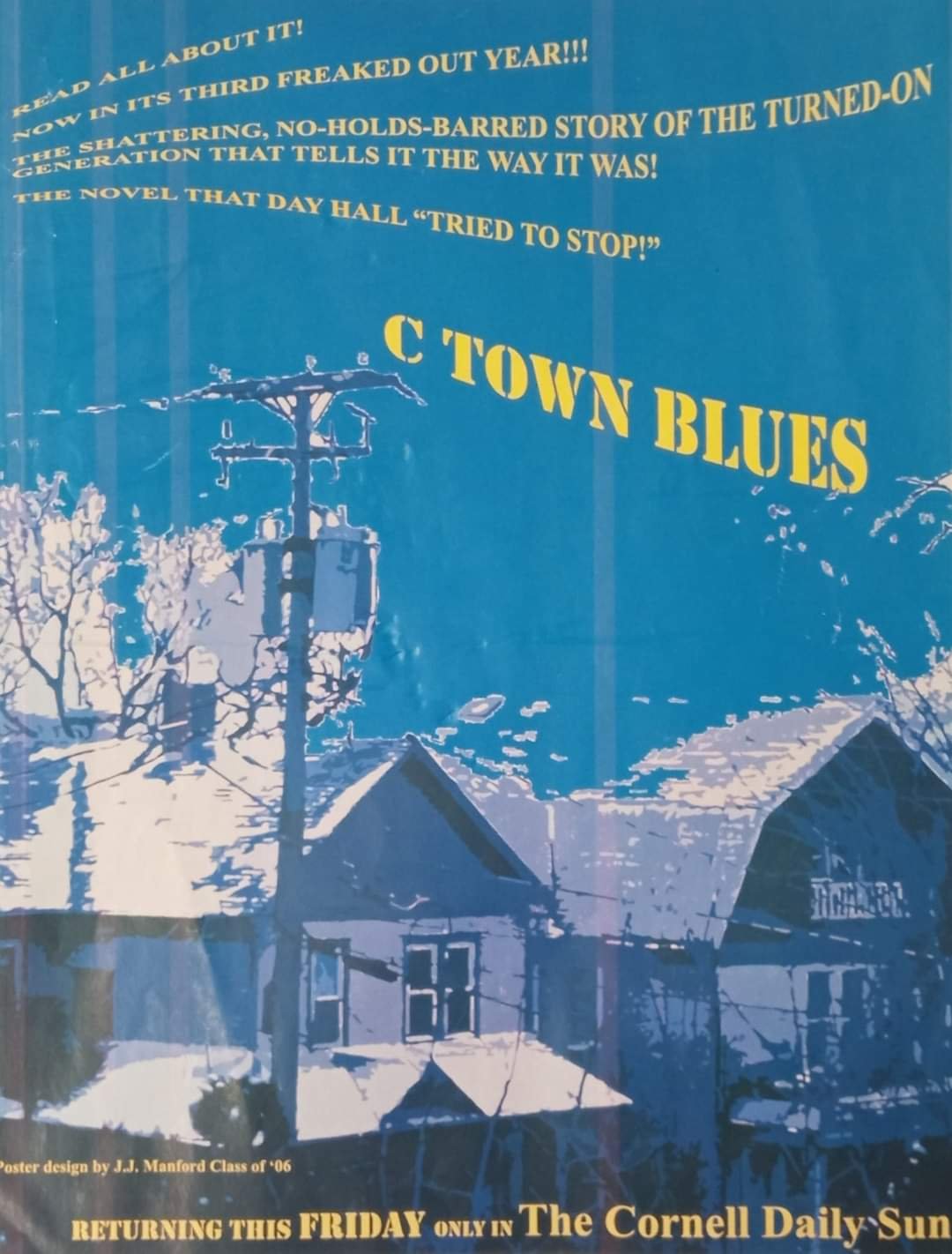

Finally, I had made a mark on Alma Mater. Even my mother, Dorrit, came to visit for the first time since 1969. In the meantime, I labored away on my book at Uris and my other, inviting extant undergraduate haunt, the Green Dragon café, in the basement of Archchitecture, with the aid of my band of devoted Risleyite assistants, aka The Munchkins (a tradition that continues up until the present day here in Latvia). And wrote “C Town Blues,” my 26 installment novel about my thrilling/crazed/heartbreaking undergrad years for “The Cornell Daily Sun,” gloriously illustrated by my uber-talented former Munchkin and surrogate son, now rising star of the New York art scene, J.J. Manford ’06 (who I am now writing a book about: see www.gordonsander.com/rooms). And finally exorcised the Sixties. And mounted two massive photography exhibits, “My World,” and “My Cornell” at the Fine Arts Library beneath the expansive dome of Sibley Hall.

I also found a new home for my works at Sage House, once the site of the Cornell Infirmary, now the headquarters of the Cornell University Press, which published two of my books, including Serling, which had gone out of print and the Press reprinted in a gorgeous new edition, and The Frank Family That Survived (see attached), both of which are still gloriously in print. Thank you CUP!

At the same time I also fell in love with Cornell and its campus, and the gorges, and its soaring intellectual and spiritual horizons, as symbolized by McGraw Tower, once again, just as I did when I first beheld that iconic needle thirty odd years before as a bright-eyed, hopelessly naive frosh.

And this time Cornell did finally live up to its promise for me.

All roads lead to Cornell indeed, even though in my quixotic case, I had to retread those roads and paths in order to maximize the value of my original tuition—including the tuition I lost after I was suspended! Then again, the arc of my life and career has never quite resembled that of anyone I know.

So be it. I think Eza Cornell, who was something of a non-conformist himself, would have approved.

****

BOTH of the aforementioned, quite disparate eras are represented by the lovingly curated collection of 14 essays, articles, and undergraduate disjecta membra archived in this ivy-covered sector of The Sander Zone, so to speak.

The first era—the Deranged Years, you could call them—are represented by the unforgettable Letter to a Cornell Professor Explaining Radically Overdue Paper (1970), which I left at the door of one of my hapless professors in the winter of 1970, by way of a cover note explaining why I was submitting a paper several weeks late: “…Initially I consulted with Dan Chilowicz as to the theoretical approaches which would be most in character with the type of inquiry launched by the class this term. His surrender to a gnawing perplexity was a discouraging interruption of my labor…This project was at first an annoyance, then a silent fascination…” And so on.

It didn’t work. I still got an F. Still good for a laugh and a retroactive shudder to realize that I actually wrote that, no less had the nerve to drop it off at my baffled professor’s snowbound doorstep that dark long ago morning at the end of the Sixties—at least my Sixties—in December 1970.

Farewell Aquarius.

Then there is “More April ’69 Blues,” one of the guest columns I wrote for the “Sun” on one of my return visits to The Hill in 1989 to coincide with the 20th anniversary of the Straight Takeover, recreating that horrific weekend: “…And then marching over to Barton [Hall] and watching it fill up with five, six, eight, ultimately 12,000 Cornellians…and then watching, and not quite believing, as the AAS leadership entered in its best Cleaver-Seal-Panther fashion and hearing the assembled students gasp simultaneously as we learned from [AAS leader] Tom Jones what they planned to do if they didn’t hear from [University president James] Perkins by midnight…’We have hand grenades,’ he declared, ‘we have machine guns…Cornell will die tonight.”

It didn’t that long night at Barton, when I wound up joining the two thousand students who decided to join the spontaneously declared “occupation” of the massive drill hall. If President Perkins had decided to call for assistance from the hundreds of state police and other blue meanies who were gathered downtown and ready and eager for the chance to crack some student heads, who knows what would have happened. Fortunately, the overwrought president, who resigned shortly afterwards, had the presence of mind not to. But it was a close thing. Cornell definitely dodged a bullet that night. Or should I say, a hand grenade.

And then there is “On Closer Examination,” the profile of the late great Howard Andrus, the director of the long gone University Testing and Guidance Service and my homage to the one Cornell administrator who cared about me whilst I was flailing about during that dreadful penitential term in the Division of Unclassified Students, after I stumbled into Andrus’s Barnes Hall office after hearing good things about him and his arcane but evidently reliable battery of tests, and who recognized my potential and later helped ensure that I did return after the Committee sent me packing.

First I agreed to take the day long, personalized cocktail of aptitude and personality tests that Andrus, a stalwart believer in the value of testing concocted for me.

The initial test results were not especially reassuring. Thus the results of something called the Guilford-Zimmerman Temperament Survey, which measured things like “emotional stability” (result: 10%), “objectivity” (4), “restraint” (70), “ascendance” (50), introspectiveness (92). “Put very crudely, I was an emotionally unstable, deeply introspective, and somewhat lethargic elitist with little if any capacity for objectivity—qualities I shared with many of my spaced-out contemporaries. ‘Don’t worry Andrus assured me with a smile, ‘You just have to do a little growing up.’”

He was right.

Then, moving out of Cornell’s—and my—Sturm und Drang period, there are the columns I wrote for the Alumni News about the morphing student zeitgeist and the onset of the New Vocationalism, as it was called, as exemplified by “Where is the Cornell Heart?,” the column I wrote in the spring of 1973, as I was finally about to graduate myself from the palpably calmer, if more boring Cornell that I had entered.

Apathy was the word at the time: “Apathy, cynicism, and disillusionment certainly seem to have taken their toll on that last remaining bastion of student power, the University Senate. Starved of attention from the student body, deprived of real issues to act on, the Senate had difficulty maintaining its reputation as a vital campus institution.”

However all was not lost: “A nostalgia craze swept the campus, bringing with it monstrosities like ‘Freddie’s Choreographed Rock ‘Roll Show.’ A 48 hour dance marathon proved authentic enough: at least one hapless participant was dispatched to Gannett Medical Clinic with a case of water on the knees. A few dapper daddy-os sported oxfords or saddle shoes.”

One of those dapper daddy-os was me, actually. When I appeared at Uris Library for the awards presentation for the aforementioned book collection contest that spring, I was wearing oxfords and pleated pants: I had escaped back to the Jazz Age.

Then, from 1974, the year after I graduated, and my first official year as a bona fide freelance, there was “The Hidden Landscape of Academic Failure” (my original title), my acidic takedown of Cornell’s advising system—and, by extrapolation--of Cornell and the chilly new vocational ethos itself: “At Cornell, the problem of academic failure is rather well-hidden, emerging full-blown for the student only after the completion of the semester’s classes”—as it had for me, after I had slept and smoked my way through that depressing fall 1969 term, and I had belatedly come to my senses and was psyched for the following term, and it was too late to do anything about it—“and the reporting of final grades. By that time university and college administrators can do little else but leave the affected students to the mercy of the dreaded committees on academic records.”

You’re telling me!

There was more, much more: “..The new vocationalism seems to have created a powerfully polarizing conformity: those who, in spite of the poor quality of the academic support system, can fix their vocational star and guide themselves by it.are thought of, and think of themselves, as ‘together.’”

Then there were the unfortunates who could not fix their star. “Some leave school altogether. Others hang on.” Cue dirge-like dramatic background music. “These are the young men and women one notices at night in the dim corners of Collegetown bars, slumped in chairs, nursing beers, dragging on cigarettes, a new lost generation of sorts. Some will get by, easing their way into ‘gut’ courses, just barely maintaining the minimum cumulative average required for good academic standing. Others more oblivious to their fate, will let themselves fall below their respective colleges’ waterlines (usually a C-minus) and be placed on final warning, suspended, or expelled.”

As the recipient of three of the abovementioned academic actions (Warning, Final Warning, Suspension), I could sympathize.

Ok, perhaps I was being a little melodramatic.

To be sure, my expose was not totally negative. I did have some recommendations: “Bring back mid-term grades…abolish the curve…abolish letter grades for underclassmen..resuscitate the faculty advising system…Design more courses for non-majors..”

“I don’t kid myself,” I opined at the end of my seven page long broadside. “Putting the assorted changes outlined above into effect will not eliminate academic failure at Cornell. But they might help control it, and in the process reaffirm the university’s commitment to humanistic education.”

Needless to say none of the above recommendations were acted upon—at least as first. (The advising system was overhauled years later, as much for economic reasons as compassionate ones: Day Hall realized that when it suspended or expelled all those students it also lost their tuition and fees.)

But the piece certainly got the attention of Day Hall: my editor, John Marcham, saw to that by making it the centerpiece of that issue. I also had my first experience of someone whom I had befriended and interviewed in the course of researching the article, in this case, a nice chap who happened to be one of the too few student advisors at the College of Arts and Sciences, who had spoken to me for the article, and refused to speak to me or take my calls after it was published.

That smarted. But I was learning.

Had I fixed my vocational star? I wasn’t sure. But I was having fun as a journalist, and making a living (of a sorts), and, in my own way, helping to change the world, particularly the hidebound world of higher education. I also seem to have stumbled onto an attractive journalistic specialty, as well as one which needed new blood. That year I also began writing features for national magazines about important, overlooked, campuswide trends, like “Campus Cops: Constables or Carabinieri?”, the feature below which I wrote for College Monthly, the new glossy national magazine for college students--oh yes for the days of glossy magazines!--about the epidemic of campus crime and what various colleges and universities and how their respective campus security forces were dealing with it, or not.

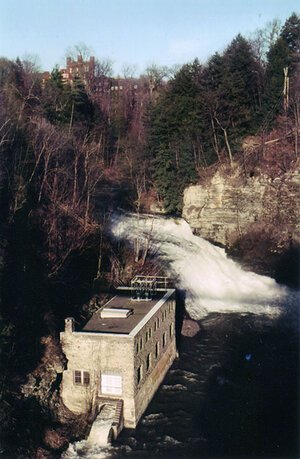

I also used Cornell, which had recently suffered the theft of the entire arsenal of its Army ROTC unit (!), and its well-trained if low morale campus police force as one of my case studies for that piece. It was also while I was researching that piece, while riding shotgun with a Cornell policeman that he received a call about the latest student who had committed suicide by jumping into one of the gorges that bisect the campus. Gorging out, that then all too common ritual of Cornell life used to be called, in the days before the college fathers moved to install nets under the bridges leading to the campus.

Ah yes, gorging out. One thing about the “old” Cornell I definitely do not miss!

Anyway, I had gotten my start as an education writer. Two years later I was a regular contributor to the Ideas and Trends page of The New York Times, specializing in trends in higher education.

So I guess I got something out of Big Red after all.

Still, I can’t say I really missed it.

****

I did miss SOME things about the “old” Cornell, though, as I confessed in “Ruminations of an Ex-Space Cowboy,” the poignant essay I penned for the “Sun” during one of of my occasional returns to the Hill in January, 1987.

Particularly the Ivy Room jukebox.

“Why did they have to take ‘Let’s Spend the Night Together’ off the Ivy Room jukebox?” I mused in my squib, which I wrote partly in response to the undergrads I encountered on campus who felt that they had missed out on something by missing the Sixties, as well as my own selective nostalgia.

I wrote that piece at my favorite desk in the Andrew Dickson White room of Uris overlooking Libe Slope: “From my writing window in Uris I see hapless freshmen slip and slide over themselves as they trudge up Libe Slope to registration. Others do a comical, mincing double-step as they try to avoid falling down (with mixed success) on the equally treacherous way down.”

“At least they have women down there now, I see, as an unfortunate co-ed”—I still called them co-eds!—“caught in the vortex of an icy devil-duster, does an involuntary Westminster waltz before beginning her zero to 60 descent.” I remember doing one of those!

“Nostalgia is fine, but I refuse to visit my freshman room (UH 4209); it still pops up often enough in nightmarish recollections of my Kafkaesque, second term as an Unclassified student, walking a slack, bureaucratic tightrope between Architecture, Arts and the U.S. Army…”

“I don’t see too much to be nostalgic about,” I continued, “or know too many sane progressive humanists to be nostalgic with. And I am too busy with my own work anyway. Farewell Aquarius.

“I do miss the music, though I miss Janis. And Jimi.

“But,” I advised all those “Sun” readers who felt that they had been born too late, as many students during the 80s did, “there are still plenty of beta waves out there if you know how to catch them. And the Stones are still around. Who knows, maybe they’ll play Cornell again as they did in ’65.

“In the meantime,” I mused, “will someone please put ‘Let’s Spend the Night Together” back on the Ivy Room jukebox?”

Sure enough a few years later, the jukebox—remember jukeboxes?—was gone, too, replaced by a mind-numbing flat screen permanently tuned to ESPN.

Oh the horror…the horror.

****

AND then suddenly, fifteen years, several eras, including a six year London stint, later, there I was again on the nauseatingly-cum-exhilaratingly familiar long distance bus from New York back to Cornell again, in September 2002. Except that this time I was really moving BACK to campus, to my new stint as guest suite artist at Risley Residential College for the Performing and Creative Arts.

And what was taking place when I arrived? An authentic medieval jousting contest.

“This must be the place,” I muttered to myself as made my way past the medieval-attired jousters and settled into the invitingly high ceilinged guest suite, which had once been the home of the mistress of the house when Risley was a women’s dorm.

It was indeed, as I gushed in another guest column I wrote for the “Sun” in May 2003, about the unique position I had lucked into, as well as what turned out to be my home for the next two years.

“I have one of the oddest faculty-or quasi-faculty—positions at Cornell,” I enthused, in “The Risley Sanction,” the latest of my long-running series of guest appearances in the venerable campus rag, “as well as one of the coolest. And what makes my job so anomalous also happens to be what makes it so cool. As one of the two guest suite artists, or GSAs as we are technically known in Ris-speak (we’re also known as Gizzas in Ris-speak, but you don’t want to go there) I work directly for the student body of Risley College. If the 190 students who live and hang at Risley don’t like the programs or vibes I create, basically, I don’t eat…

“’Are you sure you want to do this?,’ a friend of mine who attended Cornell in the late 80s asked me as I prepared to undertake my voyage back there, i.e., back to Cornell and Risley. ‘You know, when I was there [at Cornell] it [Risley] was a pretty strange place,’ he said, arching his eyebrows for emphasis.”

It was. And I loved it, as I wrote. (I also ate. Too well: I gained 10 pounds almost immediately thanks to the overflowing twice daily eat-as-much-as-you-want meals served in the dining hall.)

To be sure, I didn’t love it right away: “The nadir came one Saturday night when, surrounded by expressionless Ris-zombies I did my laundry in the communal room for the first time and had to extract another evidently deceased student’s long-abandoned wash, triggering at least one memory of my student years that I had rather left alone.

“’You’ve come a long way, baby,’ I muttered.’

But, as I wrote, I got into the peculiar Risley spirit soon enough, and wound up running with the position: “I created a newsletter for the college. I gave a tongue-in-cheek lecture series on my life and times. ‘Diary of a Head,’ I whimsically called it. I produced and hosted an enthusiastically attended Twilight Zone marathon for which I did my first all-nighter since the days when as an undergrad I used to stay up watching reruns of the classic tv show.

“More mystifyingly, one cabin-feverish winter’s night I was moved to pen a Risley ‘anti-cheer’ which three of my equally mad neighbors enthusiastically practiced and performed before an open-mouthed session of Kommittee [the weekly college self-governance meeting]:

“Boomalack, boomalack, boomalack abeam/Riff-raff, riff-raff, riff-raff-ream!/If skidi wahoo wah/ RISLEY RISLEY RAH! RAH! RAH!

“…So what’s it like my skeptical Cornell alumnus friend asked me recently.

“Well, it’s sort of a cross between Animal House and Paper Chase, with a touch of Fame thrown in,” I wrote, citing those then famous Hollywood films about, respectively, a wild early 60s frat house, law school, and New York’s glittery High School for the Performing Arts.

“Nothing strange about it at all,” I concluded in the piece, which is also featured on the Risley website for those who are interested in understanding the college’s quirky ethos . “In fact, it’s a pretty cool place.”

It was, and still is.

Indeed Risley was so cool, and I wound up becoming so attached to it, as well as Cornell, that I decided to stay in Ithaca after my two year run as GSA was up and moved to an uber-cool apartment in Cayuga Heights blessed with its own stream several blocks away, whence I continued to involve myself with the college, drafting my student assistants from Risley and hosting my annual Hanging Out “course” for Risley Nation. The grateful Risleyites even voted to grant me a new title, Artist in Orbit, to signify that I was still Out There, but close by.

Thus “Hanging Out 2011: A Retrospective,” the tongue-in-cheek chronicle of one of those all-night “courses” which I hosted-taught in 2010, when I was Artist-in-Orbit, by former Munchkin Scott Reu ’11, “cosmic adjutant to Gordon Sander,” also included here. It’s pretty funny. It also gives you a good idea of why I loved, and continue to love Risley.

“10 pm. Almost 20 Hangers file into the TV room for the first event of the night, a Twilight Zone-a-Thon…Gordon tells us that his first Hangers were LSD-powered Cornellians in need of a leader. They travelled around campus, looking for wonders in whatever places they could find them, only to end up at the top row of bleachers at Schoelkopf field at 5:30 am, anticipating the sunrise. By 10 am when the sky was already light, but they had not yet seen the sun….One of them looked up to discover that they had accidentally positioned themselves on the wrong side of the sun, facing west instead of east…

“11:40 pm. We line up to get into the bus which will take us to the Haunt, a local bar and grill. The bus driver gets lost…

“1 am. We depart the Haunt on foot, aiming for a school playground a few blocks away. The swings are almost immediately snapped up by voracious and disturbingly giddy hangers..

“2 am. Gordon gives us [his famous 20] rules for life in an increasingly freezing cold part of the park in Ithaca. Everyone huddles for warmth as we listen to Gordon tell us the importance of remembering where you put things..

“4 am. Gordon has given us some candles to light for our sunrise poetry reading.. Everyone sings ‘American Pie’ together. Tom falls asleep beneath a blanket constructed entirely of Blue’s Clues coloring book pages. At 4:45 Gordon tells us that it’s time to depart for the park [Sunset Hill, down the road from my apartment]..

“5 am. We take our candles and our poetry down to Sunset Hill, which is damp with dew and chilled. Seven people read poems and stories, and we watch as the wax on our candles melts and runs down out fingers, imparting momentary warmth. I feel a genuine, deep communion with my fellow travellers. I could see Gordon’s first group of Hangers, lost in a trip in 1970, facing the wrong way to watch the sunrise at Schoelkopf, riding a wave of LSD, [hoping] for a sunrise of a different sort…”

“6 am When we finish, the sun has already technically risen, but Sunset Park has one final parting gift for our company of tired Hangers: a gorgeous view of [Lake] Cayuga and the valley in which Ithaca sits like a jewel…”

And so it went. Thank you Scott! Yes, the sun rose that morning, as it did every time I “taught” my all night seminar in Hanging Out. (See attached photo of the assembled graduates-cum-survivors of that gathering).

True story.

And you wonder why I continued to hang out in Ithaca for thirteen years after I moved out of The Castle. I still had a role to play.

And of course I also had work to do. Ultimately, I wound up writing parts of or all of five books during my second, extended Cornell life—The Frank Family, The Hundred Day Winter War, Off the Map: A Personal History of Finland, Comeback Coach, and Citizen Kekkonen, along with C Town Blues, and seventy odd articles and essays, as well as mounting two major photo retrospectives, including one of my images of Cornell from over the years (several of which are attached here). Along with mentoring a new generation of Cornellians—and employing two dozen of them as my assistants.

Indeed, my decision to return to Ithaca to be GSA at Risley, as well as to remain—daresay I say hang out?--in Ithaca for another decade and a half, was arguably the best decision that I made in my life.

A Hail Mary move—how could I predict how things would turn out when I boarded the bus from New York to Ithaca once again in September 2002—but it worked out. Ultimately I decided to move on and in 2017 to relocate to Latvia, where I am now based.

Another dicey move, which seems to have worked out.

But hardly a day goes by when I don’t find myself thinking about Cornell and Risley, and all those kids I hung out with, and hopefully helped fix their star.

RISLEY RISLEY RAH RAH RAH!

****

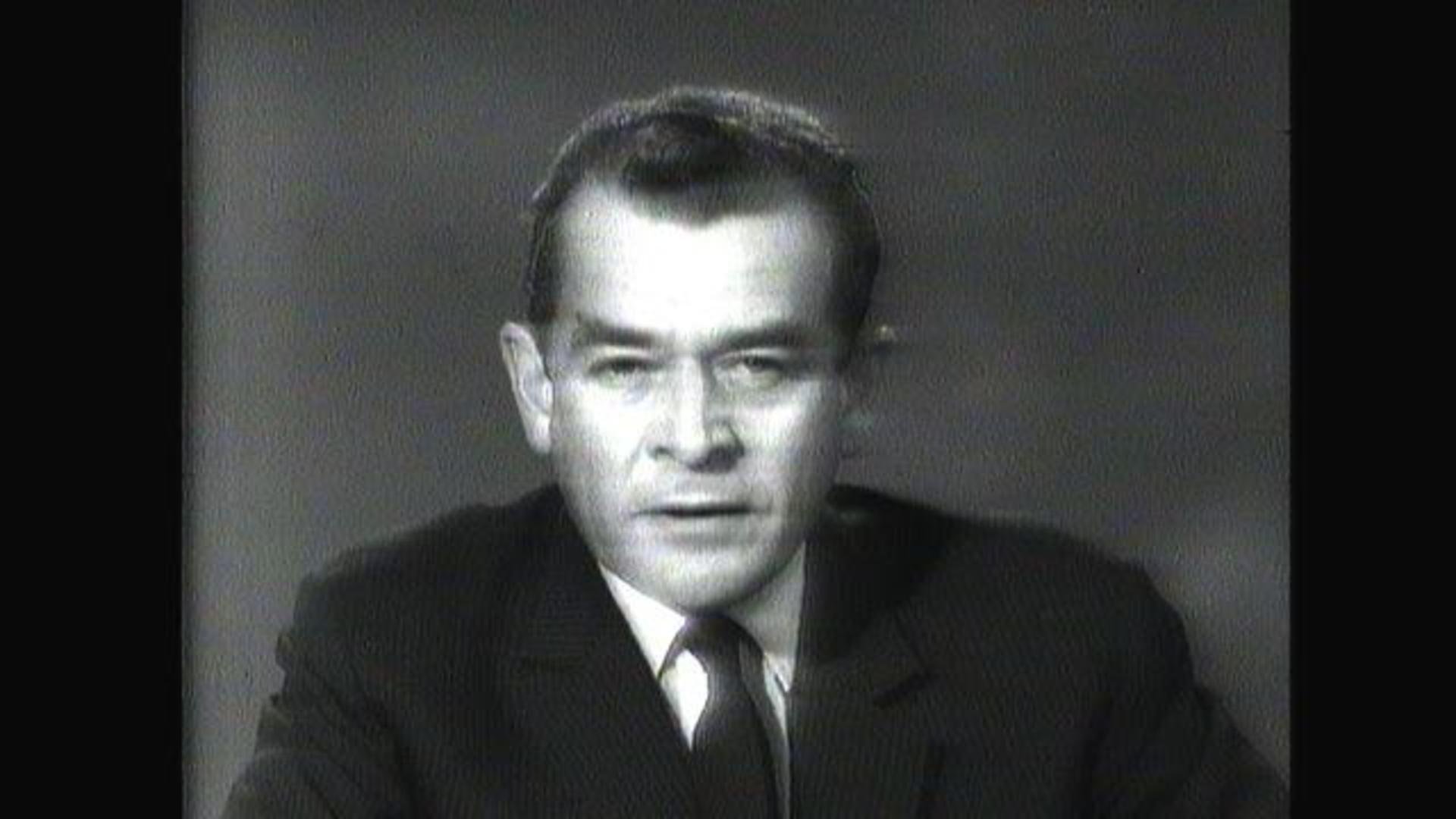

LAST but not least, my customized Cornelliana section also includes some of the forays into popular history and biography I undertook for the Alumni News, including some of the disparate Cornell alumni who I admired, like Charles Collingwood ’39, the great CBS reporter and commentator.

As well as, I think, some of my best, and most deeply felt writing.

Thus from “This is Charles Collingwood,” the profile of the late great broadcast journalist, “perhaps the closest thing that the air has had to a man of letters” I wrote for the News in 1990:

“Television viewers had a particularly good chance to see Charles Collingwood’s versatility as a reporter commentator in 1962. First on February 14 there was his famous ‘A Tour of the White House with Mrs. John F. Kennedy.’ Collingwood’s learning and elegant style made him a perfect match for the equally elegant First Lady as she showed him and millions of awed viewers the dazzling accoutrements of the Kennedy White House. For those who were lucky enough to see it, the show remains one of our fondest collective memories of the Kennedy years, the video embodiment of Camelot.

“’We’ve seen some of the ingredients of the furnishings for the White House,’ the handsomely dressed correspondent observed to the regal looking First Lady as the video couple strolled through 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. ‘Yes,’ breathed Jackie Kennedy, on cue, ‘the diplomatic reception is right next door if you would like to see it.’ Yes, the correspondent did—and so did an enraptured nation.”

Inevitably, the piece, which I wrote while I was working on my first book, about that other great CBS alumnus, Rod Serling, had a flashback to Cornell in the 1930s, care of his fellow alumnus and Telluride associate, Austin Kiplinger’ 39: “’Elegance of speech, elegance of dress, elegance of manner—that is the way I remember him.’ Kiplinger recalls that a typical Saturday evening at Telluride would have the erudite philosophy major standing before the fireplace declaiming poetry or articulating his views on the gathering European storm,” which he would soon report on as one of “Murrow’s boys,” i.e., the elite squadron of London-based broadcasters under Edward R. Murrow, CBS’s famed director of European news operations.

“And whenever one thinks of a myriad events, catastrophes and ceremonies from the 1940s through the 1970s,” the spirited profile concluded, “one hears the reassuring sign-off of the remarkable broadcaster: ‘This is Charles Collingwood…CBS News.”

Then there are the three inspired pieces I did about my favorite decade, the 1920s, including my profile of one of the more illustrious graduates from that period, as well as star-crossed, the wonderful actor and star of “Mutiny on the Bounty” and other movies of the 1930s and 1940s, Franchot Tone ‘27 which includes a memorable snapshot of campus theater life during that decade which I compiled with the aid some of the late actor’s extant thespian friends:

The future matinee idol’s interest in acting apparently was first piqued when he happened to see a flysheet in Goldwin Smith Hall calling for students to try out for the Cornell Dramatic Club’s upcoming spring production of George Bernard Shaw’s ‘Arms and the Man.’ On the face of it, the campus group didn’t have much to offer. It didn’t even have a theater—only Goldwin Smith B and a stage (if you could call it that) so small that in the words of ‘The Ithaca Journal,’ the actors had always to keep their sense of balance as well as their lines in mind, lest they lose their equilibrium and join the surrounding audience.’

“But what the club lacked in the way of equipment it made up for in enthusiasm and camaraderie. ‘We were a family, really,’ said Emily Grams ’27. ‘We did everything together.’

As I wrote, Tone was unquestionably the star of the group: “With his suave good looks and flair for repartee Tone at first blush was well-suited for comic roles like that of Buntschli,” the main character of the Shaw play. “At the same time, as the growing audience squeezed into Goldwin Smith B could see, he did equally well with heavier dramatic roles. As an admirer later wrote of the versatile performer, ‘he was the type who would make you forget that he was a college boy untried by life.’

“‘My God! Could he act!,’ Ralph Seward ’27 remembered.

Indeed he could, and did, and Tone continued to do so after he graduated and went on to the Bright Lights, dazzling cinema and theater-goers in Broadway hit plays like “Success Story” and “The Fifth Column,” and movies like “Mutiny on the Bounty,” for which the today sadly forgotten great actor was nominated for best actor in 1935, and “Three Comrades.” Those were the days when the tall, dashing Cornell-trained thespian was touted as the heir to John Barrymore.

Sadly ‘twas not to be, as I continued: “Unfortunately, Tone wound following up Barrymore’s lead in more ways than one. Somewhere between his stormy first marriage to superstar Joan Crawford, and his even stormier one to starlet Jean Wallach—or was it his second to Wallace and his third to Barbara Payton?—his work began interfering with his drinking, as they used to say. Thus the story of Franchot Tone is at once a triumph and tragedy.”

Indeed.

Then, for sheer fun, it’s hard to top the bubbly essay I wrote for the News way back in 1976, when I was just starting out, about Elspeth Huxley, the English writer, about the four years she spent on The Hill, including Risley, as an exchange student. “The Good Times: An English Woman remembers Cornell in the 20s,” the piece, based on her memoir, “Love Amongst the Daughters,” was called.

And Huxley certainly had a very good, albeit at first somewhat disorienting time at Cornell after she arrived in Ithaca at the then mostly male university in September 1927:

“She began to feel the tremors of culture shock almost immediately. On the morning after she arrived on the Cornell campus, she was awoken by someone who said she was her new ‘grandmother.’ Was this some sort of joke. Not at all. This loquacious young woman was exactly who she claimed to be. Co-ed grandmothers were a familiar fixture of Cornell life in the fall of 1927…”

Huxley’s memoir, I found, provided a clear-eyed snapshot of what campus life was like during the Jazz Age, the good, the bad, and the silly. Amongst other things, her book, which I clearly adored, was a reminder of how much campus life was dominated by the fraternity system, which she did not adore:

“Since Cornell’s social life revolved around fraternities, no single event was more important, or more electrifying than the annual fall rush. The greatest wish of Cornell’s beanied underclassmen (men had to keep their frosh beanies on all the time) was to be asked to join one of the more prestigious, or moneyed, houses. Conversely, the ultimate horror was to be rejected by them all. It all depended on who he was—or who, with luck, he might turn out to be:

“’Desirability was complex and subtle. It could rest squarely on riches—any son of the president of General Motors or Standard Oil would be desirable in the extreme…Otherwise it was a gamble on the fortunes and talents of newcomers. Who would become the future captain of football, stroke of the crew, president of the Student Council, editor of the Sun… Some students received no bids at all.

“’It was a cruel system,’ Huxley concluded,’ crueler than the British class system because it was consciously applied and even more rigid. It had caused student suicides.”

Huxley avoided the rush herself. Nevertheless she received two bids. What to do? “She decided to toss a coin for it. The second house won out. Her new sisters were overjoyed. Upon arrival at the house [she chose], she suddenly found herself beset by a pack of ‘howling dervishes,’ as she drily recounted.

“’Flailing arms enveloped us, we were pressed to bosom after bosom until I literally gasped for breath.’ The shy English girl didn’t quite know how to respond. ‘No wonder Americans regarded the British as a cold standoffish, frigid lot, barely human,” she wrote. “We were.”

Good sport that she was, Huxley also threw herself into the fervent, if relatively tame mating rituals of the day, as she vividly described: “’During the night,’” she wrote, recounting her memories of 1928 Junior Week, “’there was a good deal of going, if not actually to bed, at least to a parked automobile.’” And so Huxley went too. “’If I went on a blind date and necking was expected, necking there would be. I would not hang back like some timid prude, earning a bad name for all British girls.”

Of course she also partook of that other great ritual of the day: Cornell football. Think that college football, including Cornell football, is big today? The enthusiastic Cornell home games of today are but a patch on their electrifying, standing room only Jazz Age predecessors, as the author vividly describes:

“After we had assembled in the stadium—thirty thousand of us, I believe—there was a hush of expectancy. Then, from beneath the stands, the cheerleaders burst forth like so many toreadors, clad in white trousers and short crimson jackets and carrying megaphones.

“At first,” the agog Englishwoman recounted, “each young man crouched low to the ground, palms flat, like a frog: a mutter like the distant sound of breakers began to issue from the stands. The cheerleaders then dashed along the ground in a half-crouching position, like squirrels; the cheering slowly gathered force.

“Suddenly they sprang high in the air like so many Nijinskys,” she continued, referring to the then world-famous Russian dancer, “every finger outstretched; the cheering burst forth in a mighty roar. Each [cheerleader] behaved as if his body was a baton of some frenzied maestro of the spirit world.

“She liked the half-time activities better,” I wrote. “Then again it was hard not to. On the field below, the resplendent, booming marching bands of the contesting schools paraded and cross-paraded, sashaying to and fro in their campaign hats and Sam Browne belts until—fifes, bassoons, drums and cornets suddenly falling silent—initials of both host and visitor were spelled out in huge human letters.”

“Overhead,” meanwhile, I continued, caught up in the spirit of those long ago festivities, against which the current version of Cornell football paled in comparison, “there would often appear two aircraft, painted in Cornell colors and trailing banners, whose pilots would cut their engines, swoop low and croon in amplified voices something like ‘I’m high, high, high up in the clouds smoking Old Gold cigarettes.”

Ah yes, the Twenties. Is it any wonder that I preferred the Roaring Twenties to the (relatively) Sleepy Seventies? At least they seemed sleepy to me. Then again, anything would have seemed sleepy compared to the turbulent decade I had just lived through and which forever stamped my idealistic-cum-remember-today-is-the-first-day-of-the-rest-of-your-life world view.

Finally, speaking of the 1920s, this sector of the Sander Zone also perforce contains my epic homage to that frothy era, the essay I wrote about one of the great crazes of the decade, Emile Coue and the autosuggestion craze, for my senior History thesis. In case you forgot, autosuggestion was the workaday system of self-help which revolved around the repeated use of the phrase, “Day by day in every way I am getting better and better.”

Half a century later my lovingly written 8,000 word elegy to Coueism, as the movement was also called—my first sustained attempt at a properly researched and sourced historical essay—still reads remarkably well. My impressed advisor, Larry Moore, also thought it was very well written, so much so that he thought I should try my hand at journalism. (I also suspect he did so because he thought I was a bit too eccentric to become an academic.)

I will let you savor that entertaining item, attached below, for yourself.

There is an interesting postscript to that one. Recently, “The Washington Post,” for which I am now a regular contributor, asked me to write an essay about the Coue craze pegged to the 100th anniversary of Emile Coue’s sensational road trip across America. The resultant essay contains a number of passages lifted word for word from my undergraduate History essay: America was obsessed with Émile Coué's self-help mantra 100 years ago - The Washington Post

Full circle indeed.

Thanks! Enjoy!

“Hail all hail Cornell…”

Far above,

Gordon